A financial exchange specialist recently analyzed the rising dollar-to-won exchange rate in the Seoul foreign exchange market and the government’s urgent measures as indicators of a “third foreign exchange crisis.” This is attributed to the government’s difficulty in stabilizing the market because of a fundamental deficiency in foreign currency reserves needed for immediate injection, while the won continues to decline against the dollar due to insufficient market liquidity.

Currency exchange rates are influenced by the demand and supply of dollars and won within the foreign exchange market. In order to avoid a foreign exchange crisis, interest rates need to be increased to limit the outflow of dollars and attract inflows. Furthermore, fiscal restraint is necessary to decrease the money supply and bolster the won. However, due to U.S. President Donald Trump’s push for investment in the United States, the available foreign reserves for short-term market adjustments are essentially non-existent. Additionally, President Lee Jae-myung’s public pledge to large fiscal deficits and currency expansion is intensifying the crisis, as noted by analysts.

1st Foreign Exchange Crisis

The first foreign exchange crisis occurred mainly because of President Kim Young-sam’s desire to attain economic achievements and the improper handling of foreign reserves by officials in the Ministry of Finance and Economy (previously known as the Office of Financial and Economic Affairs). President Kim aimed to achieve a per capita income of $10,000 during his last year in office, which was 1997. His economic advisors, influenced by the semiconductor boom in the mid-1990s, pushed for keeping the exchange rate low even though there was a significant $23.8 billion current account deficit in 1996.

In July 1997, the Asian financial crisis, originating in Thailand, moved northwards. International media noted that although South Korea’s foreign reserves were listed as hundreds of billions of dollars on paper, only $2 billion was truly accessible, since money loaned to banks and companies could not be retrieved quickly. This indicated a possible government default. Investors started pulling their funds out of South Korea, leading to a sharp rise in the dollar-to-won exchange rate. South Korea barely escaped bankruptcy by seeking an urgent rescue package from the IMF (International Monetary Fund).

As part of the bailout agreement, the IMF required strict structural reforms. It urged the Bank of Korea to increase its call rate (the existing benchmark rate) from 12% at the end of 1996 to 40% in order to draw in dollar investments by providing attractive returns to international investors. The South Korean government promptly increased it to 30%. The IMF also imposed requirements for financial and corporate restructuring and limited fiscal deficits to guarantee the government’s ability to repay the assistance. Consequently, the Korean economy faced significant hardship.

The first crisis was addressed when the U.S. White House, emphasizing the ROK-U.S. alliance, urged Wall Street investors to agree to extend Korea’s debt repayment periods. Korea managed to issue government bonds because of the solid financial base created by Presidents Chun Doo-hwan, Roh Tae-woo, and Kim Young-sam, utilizing the funds to restore the failing economy. As investigations into responsibility started, officials quietly included regular citizens—who had benefited from inexpensive dollar travel due to the weak exchange rate—on the list of those held accountable.

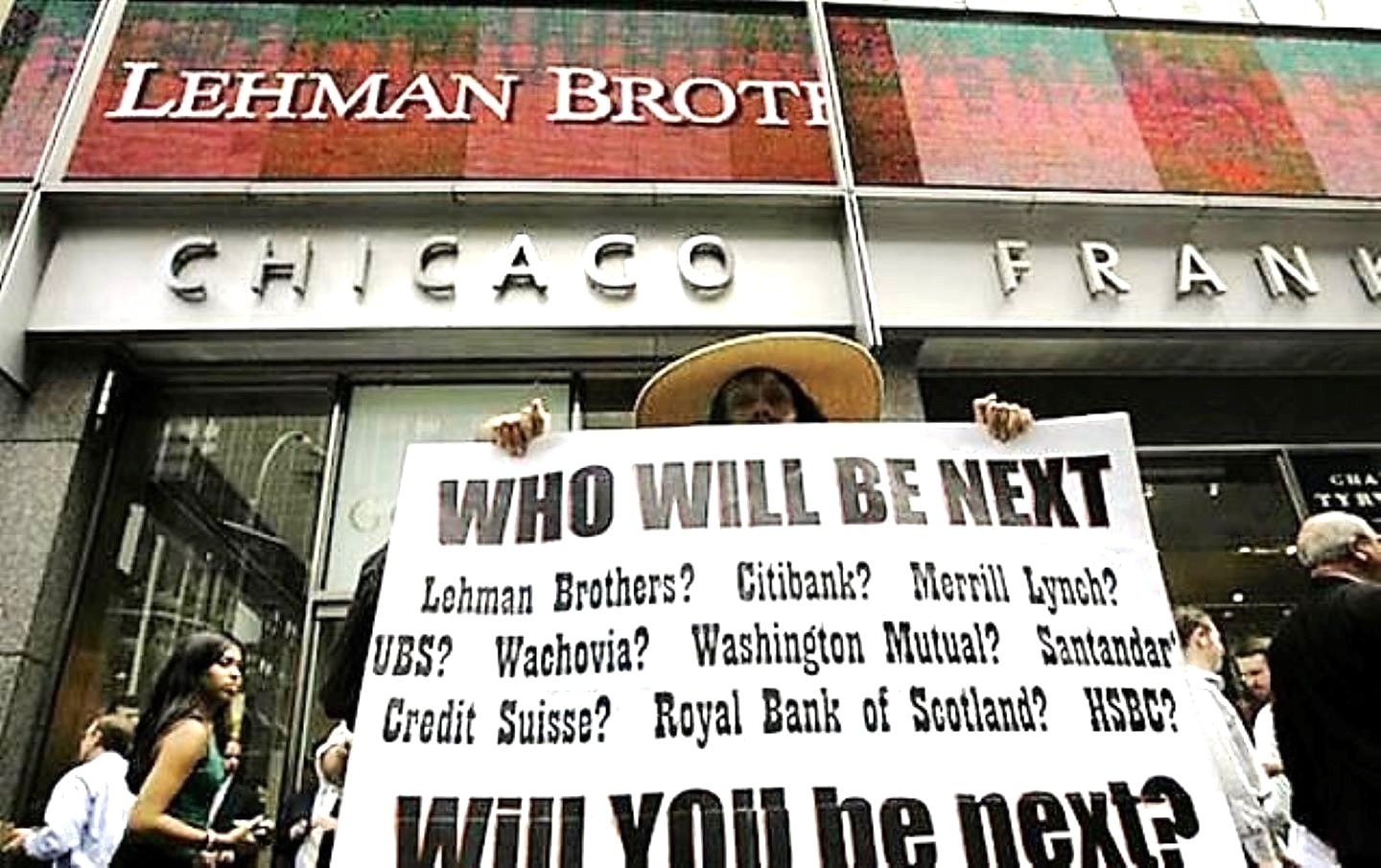

2nd Foreign Exchange Crisis

A second foreign exchange crisis arose during the 2008 global financial downturn, which began in New York. Currency values around the world, including those in Korea, experienced extreme volatility. However, Korea’s prior experience in dealing with the first crisis was highly beneficial. The economic team, which had accumulated significant foreign reserves, took action to stabilize the market whenever psychological imbalances emerged. Although adequate reserves could not halt the rising trend in exchange rates, they greatly eased concerns about a second crisis.

The government’s economic team faced challenges in maintaining foreign reserves, choosing to allow exchange rate rises instead of exhausting the reserves. President Lee Myung-bak focused on acquiring cash during the crisis and directed the economic team to prioritize obtaining dollars. Similar to the first crisis, the solution emerged from the U.S.: the Federal Reserve broadened currency swap agreements to tackle the global financial situation, with Korea being fortunate enough to be included. Following the announcement of the ROK-U.S. currency swap, the exchange rate declined, and the Seoul foreign exchange market quickly stabilized.

Indicators of a Third International Currency Crisis

Foreign exchange specialists claim that the present scenario is more similar to the first crisis than the second, due to U.S. President Trump’s calls for investment, which have put pressure on South Korea’s foreign reserves.

Under the South Korea-U.S. investment agreement, South Korea will invest $350 billion (about 514 trillion South Korean won) in the United States, with $150 billion designated for direct investments such as revitalizing the U.S. shipbuilding sector. The remaining $200 billion needs to be paid over a period of 10 years, amounting to $20 billion each year. How will the South Korean government obtain $20 billion annually? The government intends to initially utilize interest earnings from the Bank of Korea’s foreign exchange reserves and profits from the Korea Investment Corporation’s (KIC) international investments. If this is not enough, it will issue U.S. dollar-based government or public bonds.

Experts highlight this aspect. According to calculations: Korea’s foreign reserves reached $430.7 billion by the end of November. If entirely invested in 10-year U.S. Treasuries, this would provide an annual return of 4.1%, resulting in $17.7 billion. Furthermore, if KIC’s $65.7 billion in bond investments (out of a total of $206.5 billion in assets as of last year) were similarly allocated, it would generate an additional $2.7 billion each year. Together, this could cover the $20 billion annual payment.

Nevertheless, to gain this interest, Korea needs to keep U.S. Treasuries for a period of 10 years without selling them. This implies that the approach taken during the second crisis—selling hundreds of billions of dollars in Treasuries to stabilize the market during turbulent times—is no longer feasible. One expert expressed a negative outlook, stating, “Korea’s foreign reserves amount to $430.7 billion on paper, but in reality, none of it can be accessed.” Neighboring Japan, which has committed to investing $550 billion in the U.S., possesses $1.324 trillion in reserves, providing it with greater adaptability. In response to this, Deputy Prime Minister for Economic Affairs Koo Yun-cheol mentioned during a session in the National Assembly, “If the foreign exchange market is impacted, we might discuss with the U.S. to lower the annual $20 billion cap.” However, analysts believe that if the circumstances deteriorate further, the U.S. will focus on its own interests, leaving Korea’s government powerless without accessible reserves.

The Self-Imposed Injury of President Lee Jae-myung

To stabilize the foreign exchange market, either the supply of dollars must rise or the demand for it must fall. With the government unable to utilize its reserves for stabilizing the market, the available options depend on major dollar holders: ① import-export companies, ② the National Pension Service, and ③ domestic and international financial investors. This is why Deputy Prime Minister Koo and Bank of Korea Governor Rhee Chang-yong have encouraged the National Pension Service to conduct currency exchanges outside the foreign exchange market, export firms to sell dollars, and investors to avoid investing in overseas stocks. However, companies and investors are more responsive to profits and losses driven by exchange rates than to government appeals. Engaging the National Pension Service, which oversees citizens’ retirement savings, could lead to future inquiries about the “ultimate decision-maker,” no matter how it is presented.

Experts claim that, according to the first crisis, these actions are not lasting solutions. The IMF’s strict recommendations—increasing interest rates to stop the flow of dollars and boosting reserves via fiscal restraint—continue to be the main responses. International investors pay close attention to a nation’s foreign reserves and budget deficits when signs of a crisis emerge, as these factors affect their capacity to recoup their investments.

Critics among experts have pointed out that the Bank of Korea has permitted an unusual flattening of South Korean and U.S. interest rates to continue for an extended period. Elevated U.S. interest rates encourage the movement of capital towards the United States. Moreover, President Lee Jae-myung’s approach of increasing fiscal deficits is intensifying the current situation. Greater liquidity in the won leads to upward pressure on the dollar-to-won exchange rate.

Indeed, President Lee publicly announced plans to raise fiscal deficits by 478 trillion South Korean won and state-backed debt by 64 trillion South Korean won over four years (2026–2029). This would cause the national debt-to-GDP ratio to rise from 49.1% at the end of 2025 to 58.0% by the end of 2029. As national debt rises, the strong fiscal base that helped rebuild the economy after the first crisis is no longer sustainable. Has President Lee witnessed how a foreign exchange crisis—where foreigners “attack with guns”—is far more damaging than domestic financial or real estate crises managed through interest rates? Does he know that the first shift from opposition to ruling party in 50 years happened during a foreign exchange crisis?